Mauro Giuliani (27 July 1781 – 8 May 1828)

Giuliani is reckoned by many to be one of the leading guitar composers and virtuosos of the 19th century. Although born in Bisceglie, Giuliani's center of study was in Barletta where he moved with his brother Nicola. His first instrumental training was on the cello—an instrument which he never completely abandoned—and he probably also studied the violin. Subsequently he devoted himself to the guitar, becoming a very skilled performer on it in a short time.

In Vienna he became acquainted with the classical instrumental style. Giuliani would propel the guitar away from the simple accompaniment of folk songs. In 1807 Giuliani had begun to publish compositions in this style. His concert tours took him all over Europe, and wherever he went he was acclaimed for his virtuosity and, as importantly, his musical style and sophistication. He achieved great success and became a musical celebrity, arguably equal to the best of the many instrumentalists and composers who were active in Vienna in the opening years of the 19th century.

Giuliani defined a new role for the guitar in the context of European music. He was well acquainted with the brightest luminaries of Austrian musical culture and with such noted composers as Rossini and Beethoven, and often worked and collaborated with the best active concert musicians in Vienna.

While in Vienna Giuliani some had minor success as a composer. He worked mostly with the publisher Artaria, who published the large part of his works for guitar, but he had dealings with all the other local publishers, who spread his compositions all over Europe. He developed a teaching reputation as well.

In 1819 Giuliani left Vienna, mainly for financial reasons: his property and bank accounts had been confiscated to pay his debtors. He returned to Italy, spending time in Trieste and Venice, and finally settling in Rome. There he did not have much success; he published a few compositions and gave only one concert.

Four years later he returned to Naples to care for his seriously ill father. In Naples Giuliani would find a better reception to his guitar artistry than he had in Rome, and in Naples he was able to publish works for guitar with local publishers. Toward the end of 1828 the health of the musician began to fail; he died in Naples on the 8th of May, 1829.

As a guitar composer he was very fond of the theme and variations form— a musical device that had been extremely popular in Vienna. He had a remarkable ability to weave a melody into a passage with musical effect while remaining true to the idiom of the instrument. One example of this ability is to be found in his Variations on a theme of Handel, Op. 107. This popular theme, known as "The Harmonious Blacksmith", appears in the Aria from Handel's Suite No. 5 in F for harpsichord. Giuliani completed 150 compositions for guitar with opus number. These compositions constitute the core of the guitar repertoire during the 18th century. He composed extremely challenging pieces for solo guitar.

Notable pieces that stand out from his body of works include his three guitar concertos (Op. 30, 36 and 70); six fantasias for solo guitar, Op. 119-124, based on airs from Rossini operas and entitled the "Rossiniane"; several sonatas for violin and guitar and flute and guitar; a quintet, Op. 65, for strings and guitar; some collections for voice and guitar, and a Grand Overture written in the Italian style. He also transcribed many symphonic works. Even in the Twenty-first Century, Giuliani's concertos and solo pieces are performed by professionals and still demonstrate the guitarist’s mastery of technique and musical eloquence, as well as Giuliani's stellar compositional gifting for the guitar.

Giuliani's treatise 120 Exercises For The Right Hand has become a pedagogical staple and will remain so as long as teachers set about to instruct novices on the classical guitar. It is harmonically challenged as I have mentioned before, but I have actually had students (well, one) tell me that there is no earthly reason to work these 120, as they will not be oft encountered. Despite the fact that I could not just spit out an example off the cuff, I still know in the very fibre of my being that Giuliani's exercises can be spotted throughout the standard repertoire--and the non-standard as well! I know it might seem a bit self-serving for Mauro himself, but I quickly pulled the following piece from my bag of tricks.

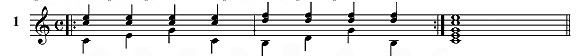

In 700 Years of Music for the Classic Guitar, Albert Valdés-Blain included his edition of a Scherzo by Giuliani that he had culled from a first edition from the very early Nineteenth Century. In the following excerpt one can see repeating rhythmic patterns. These patterns are found in the 120 as well (or at least very similar patterns.) I will be scouring the non-Giuliani repertoire to find additional examples, but this one interests me as no one plays it any more. Actually, I just did a recording of it. As simple as it is, it is a lovely little piece and despite the fact that it is something most second or third year students can play with one hand, I found it fun and a nice vehicle for my interpretive output.

The second measure in the excerpt is exercise one, plain and simple -- actually simpler. The bass remains constant -- as does the upper register! Measures seven through eight and ten through twelve are, I believe, to be found in exercise twenty-nine. I have included these (one and twenty-nine.)

No comments:

Post a Comment