Tone Ranges and theThird

You're sitting down to a new piece. You've made it a point to check the key signature and you've even checked to see the time signature! That's more than some poeple do, believe it or not. Another useful piece of knowledge to have is one that is often overlooked as well. What is the tone range?

Tone Range sounds like a fancy name for something awfully complex. Not so. All the tone range is is the notes including and falling between the highest notated pitch in the piece and the lowest.

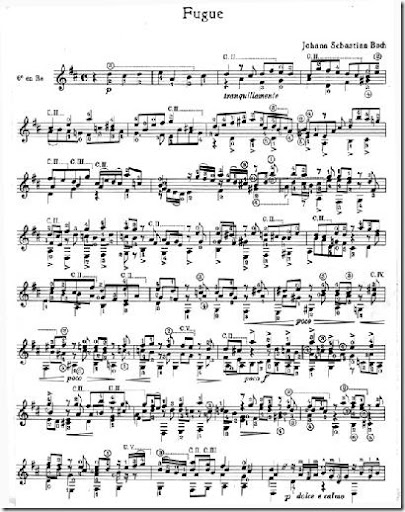

In this Back piece, the fugue from 'Prelude, Fugue and Alegro', the tone range, after a quick scan, appears to be the D an octave below middle C up to the B two octaves above middle C. (I say appears, because all we have here is the first page of the score.) Being that the piece is in D major, this is a reasonable tone range. One can expect a tone range to span a common interval such as an octave a fifth or a fourth. (usually in multiple octave spans in instrumental music.) This spans a sixth, but you will note that there are more A's (outlining the perfect fifth) than the small number of B's.

Okay, why is this an important piece of knowledge? Well, right away, bazrring any fingerings edited in for tonal variety (like playing a higher-ranged melody on the D string for the fatter sound) there should be no excursions higher than the seventh fret or so. This knowledge can have a very soothing effect on a nervous student! It will also mentally prepare you for finding some of those 'harmonizing notes' in that area of the fretboard.

Thirds. The colorful interval.

Why are thirds colorful? Well, without the third, major and minor chords... they just wouldn't exist. ALl our music would be either perfect intervals or dissonant clankings like tritones. Yeah, the sevenths would be noce, but we'd always be seeking a resolution.

Thirds are the most common form of vocal harmonization, and as instrumental music is often sited as an imitation of vocal stylings, you will often find strings of thirds in polyphonic instrumental pieces. Look at the piece above, you'll see thirds and their inversions --the sixth -- all over the place.

Thirds have shapes just like all the other intervals. Note the picture to the right. This is a major third, A (sixth string, fifth fret) and C# (fifth string, fourth fret.) When ever I see a major third in music, I think to myself "I'll be using two consecutive fingers on fret apart on adjacent strings to play that!" I'm most often correct. Open strings can throw this assumption into a ditch. BUT, it is easy to see where an open string will come into play.

Thirds have shapes just like all the other intervals. Note the picture to the right. This is a major third, A (sixth string, fifth fret) and C# (fifth string, fourth fret.) When ever I see a major third in music, I think to myself "I'll be using two consecutive fingers on fret apart on adjacent strings to play that!" I'm most often correct. Open strings can throw this assumption into a ditch. BUT, it is easy to see where an open string will come into play.

In this photo to the left we see a minor third. Once again, the sixth string A is being fretted, though now by my third finger. The fifth string is being fretted on the third fret, or C natural. I could stretch and use consecutive fingers, but why break a sweat? The first finger is so more open for business! So, when I see a minor third in the music, I know my hand will be assuming the position as seen in this picture. Once again, open strings upset the applecart, but like I've said, they're easy to spot.

In this photo to the left we see a minor third. Once again, the sixth string A is being fretted, though now by my third finger. The fifth string is being fretted on the third fret, or C natural. I could stretch and use consecutive fingers, but why break a sweat? The first finger is so more open for business! So, when I see a minor third in the music, I know my hand will be assuming the position as seen in this picture. Once again, open strings upset the applecart, but like I've said, they're easy to spot.

By knowing where the intervals fall under the hand -- like with these thirds, major and minor -- your reading gets faster. You don't have to think about the notes, just the shapes they form.

No comments:

Post a Comment